Gerald Slavet: 1970

In August of 1970, the Washington Post ran a feature article on Gerald Slavet chronicling his three-year stint as Artistic Director of Wayside Theatre. The author writes at length about the change in the life-style the Slavets adopted when they re-located to rural Middletown, Virginia. “The Slavets have made the hard choice, leaving the streamlined city for life in an old farm-house; doing their own planting, cooking, canning and freezing. They also left the life of producing plays in the city where it is easier, to produce plays in the country, where it is hard.” The article acknowledges that Slavet was quite aware of the differences he would encounter with the Virginia audience “where there is no tradition of theatre” and where problem or serious plays are not the norm. He reveals that the majority of Wayside’s audiences come from nearby towns and are “farmers, tradesmen, craftsmen and construction workers. There are not many doctors, lawyers or engineers, those members of the great middle class which is always given the credit for the successful re-emergence of regional repertory theater since World War II.” The writer notes that, despite this divergence of backgrounds, Slavet desired to “build a professional theater that will draw audiences from a wide area for the excellence of its productions.” It further mentions that Slavet wants “to perform Ibsen, Strindberg [and] Shaw” but confesses he is more practical now than he was a few years ago, and takes more seriously “the audience’s demand to be entertained, but [he] refuses to compromise his standards for producing quality theatre.” To help overcome this gap in background and training, “Slavet is holding audience-actor discussions on difficult plays. And, it is this approach he credits for last season’s acceptance of ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?,’ which is heavy stuff for Middletown, [and] to discussions which aired out the reservations and/or praise of members of the audience.” Slavet believes this approach has worked well, as “In the last three years, the theater’s attendance has risen markedly, and it has operated in the black on a frugal budget of less than $50,000” (Secrest. “Theatre in the Wild ….” TWP. 16 Aug. 1970).

Another reason for Wayside’s success under Slavet’s leadership was that he attracted many fine actors from Washington as well as New York to perform at the theatre. One of these actors, Morris Strassberg, was granted a leave of absence from the Broadway run of Awake and Sing in order to appear in Wayside’s production of The Price (Eller. “Morris Strasberg: ….” NVD. 4 Aug. 1990).

Credit is also given to Slavet’s work in other areas than his Artistic Director duties.

Under Slavet's leadership support for the theater has grown, as has the range of

its activities. After the 13-week summer season ends … Wayside will offer drama workshops for adults, teenagers and children …. A nice by-product of such a program

is an increased community enthusiasm for various programs: a film festival, and a traveling production to schools in the area (Un-named Source. c. 1970.)

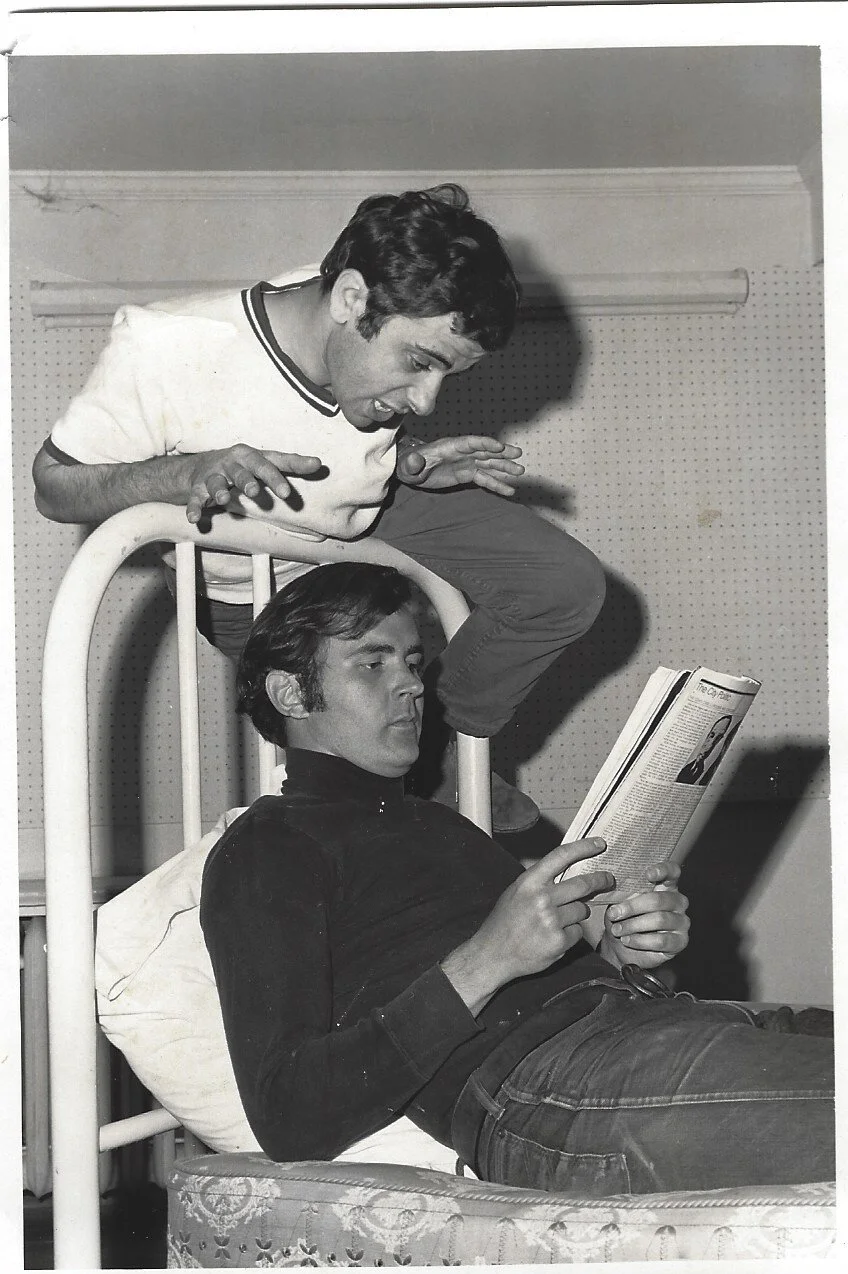

The Knack. June 23 - July 5, 1970. Johnny Arman, Reathal Bean

Slavet’s devotion to developing local interest is exemplified in his 1970 production of The Great Sebastians in which several local actors were cast. There is no record if any of the local talent featured in this production had attended any of theatre’s acting classes, but it is known that all of them had performance experience having appeared at Winchester’s Bark Mill Theatre.

Slavet had a driving passion for using theatre and theatre techniques as teaching tools in the classroom. One of his “pet projects is a course for teachers, not merely to increase their knowledge of the theater, but to teach them how to dramatize the subjects they teach so as to challenge their students minds more fully” (Longaker. 23 July 1972). Slavet worded this concept slightly differently when he advocated the use of theatre techniques in the classroom to a group of teachers.

Heaven knows the teacher is a performer. We think certain theater techniques

can help him be more exciting and creative in the classroom through better use

of his voice and body. It might not even hurt for him to know how to be able to

upstage a pupil occasionally (Hudson. “ ‘Born Yesterday’ ….” DNR. 26 June 1972).

After making this statement, it was announced that ten high school and elementary teachers had completed the three-week course in techniques of play production in a class conducted by Slavet as part of the summer program offered by the University of Virginia’s School of General Studies. (Keating, R. “Wayside Review.” TWaS. 23 July 1970).

One of the most interesting items found in the 1970 scrapbook is an extended article on the many duties of a stage manager. These responsibilities are dealt with in great detail based on information gathered from an interview with Wayside’s stage manager for that season (Eller. “Stage Manager ….” NVD. 23 June 1970).

The Great Sebastians. July 8 - 19, 1970. Joanne Walton (L), Margie Lewis, Gloria Biddle.

The many activities of the theatre continued to be promoted by the local papers, either with announcements for upcoming productions or with reviews of the performances. One announced that The Owl and the Pussycat was “a fine start for a new summer season … and is a highly recommended one, too!” (Keating. “Wayside Review.” TWaS. 11 June, 1970). In a review for the same show, another writer advised people to stop by the Curtain Call for pizza as, “It’s some of the best we’ve tried in this area!” (Eller. “ ‘Good’ and ….” NVD. 12 June 1971). Another review announced that Clinton Atkinson, who is scheduled to direct The Knack, Wayside’s second show of the season, arrived at “… Wayside Theatre after receiving the kudos of New York critics for his recent directorial efforts …” (“ ‘The Knack’ Next ….” TWaS. 18 June 1970). The writer continues by acknowledging the difficulties faced in staging this work, but recognizes that the director has “discovered a non-stop, growing pace which contributes to the frenetic action, without beating it to death” (Keating, “Wayside Review: The Knack.” TWaS. 25 June 1970). Being more specific, another writer clarified the title of The Knack by saying the plot deals with “the knack of seduction” (Eller. “ ‘The Knack’….” NVD. 25 June 1970.).

The Great Sebastians, the season’s third play, won high praise for the way it began, as it required the male actor of the mind-reading team to walk

… up and down the aisles of the Wayside Theatre, selecting random members of

the audience and [selecting] objects in their pocket for her (the other member of

the team) to identify while she is blindfolded on the stage … Much of the comedy’s hilarity stems from the revelation of how they perform these tricks …” (“Mindreading

Act ….” TWaS. 2 July 1970).

Included in the cast of The Great Sebastians were a few local actors who had experience in Winchester’s amateur productions. “These included Marjorie Lewis and Beatrice O’Connell familiar to Bark Mill Theatre audiences and Mrs. Gloria Biddle, a drama teacher at James Wood High School (“Wayside Production Stars …” WES. 6 July 1970).

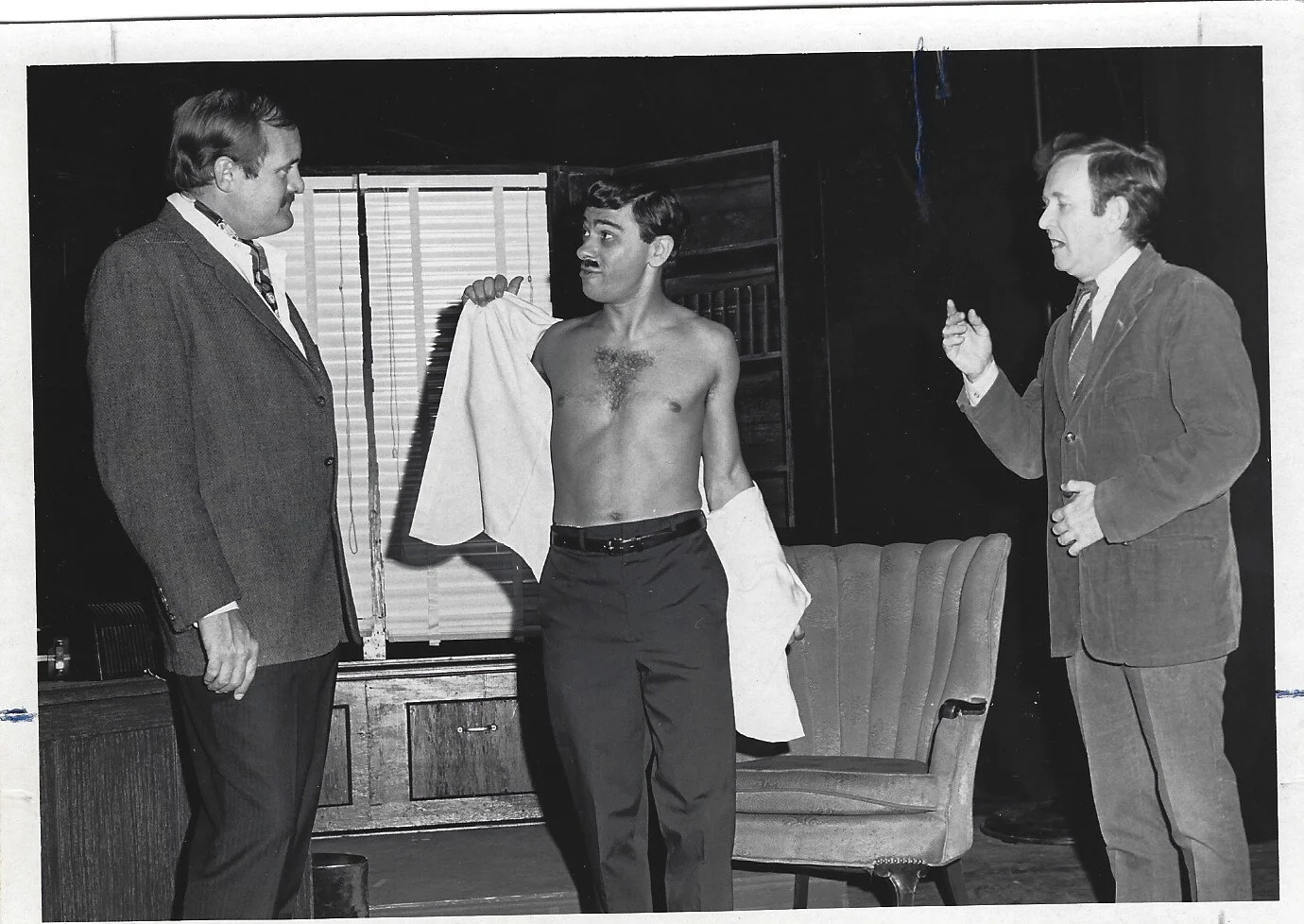

You Know I Can’t Hear You When the Water’s Running. July 21 - Aug. 2, 1970. Frank T. Wells (L), Johnny Armen, Charles Hudson.

The fast pace of You Know I Can’t Hear You When the Water’s Running, a compilation of four short plays, was praised by the reviewers. Directed by Clinton J. Atkinson, who had received NY kudos for his directing, he received equal praise from local writers. “There is so much that is praiseworthy in Clinton Atkinson’s direction: A swift but intelligent pace that knows exactly when to slow down, and misses none of the comic tempo that lies at the heart of the play’s reality” (Keating. “Wayside Review.” TWaS. 23 July 1970).

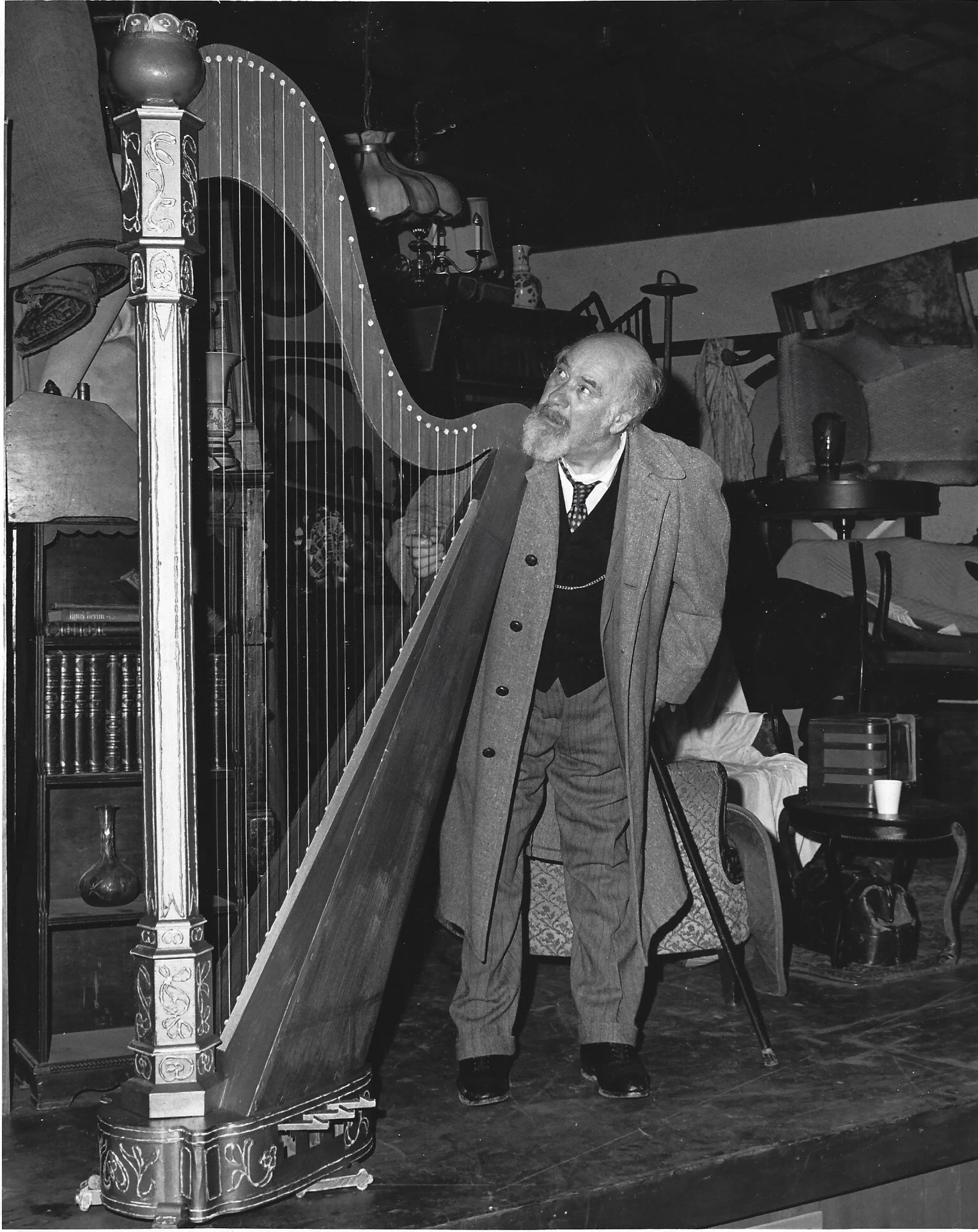

The Price. Aug. 4 - 16, 1970. Morris Strassberg.

It wasn’t just acting that reviewers recognized. The set for Arthur Miller’s play, The Price, receives almost as much praise “for its magic” as does the work done by the actors. One reviewer states that New York actor, Morris Strassberg, “is so touchingly real and comical in his wisdom and insights, that the role might have been written for his talents” (Keating. “Wayside Review.” 6 Aug. 1970). In order to take part in The Price, Strasburg took a leave of absence from Awake and Sing, the Broadway show he was performing at that time, as The Price was a play he had always wanted to do. “It was so worth it,” states Strasburg positively of his time in Middletown. “The atmosphere here is lovely. I feel so at home at the Inn. They have adopted me … I never saw [this friendliness] before. It’s lovely to see it …” (Eller. “Morris Strassberg ….” NVD. 4 Aug. 1990).

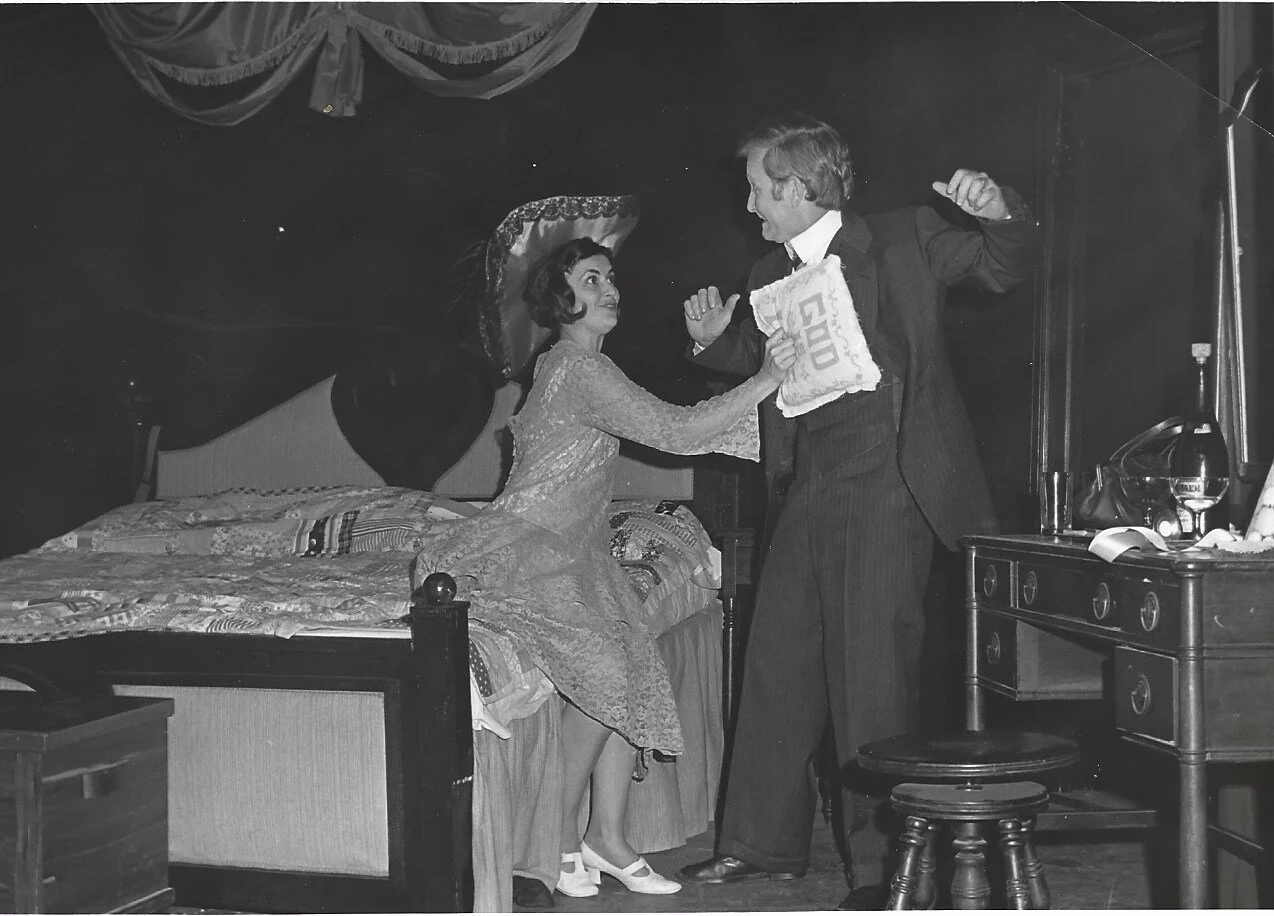

I Do! I Do! Aug. 18 - Sept. 6, 1970. Mitzi Noble, Charles Hudson.

But, it was I Do! I Do!, the closer for the 1970 season, that was the summer’s highlight. The final sentence of a reviewer sums up his reaction to the show as well as the season, “Kenneth Kimmins has directed the musical honeymoon with enough touches of style and inventiveness to keep the love affair between his actors and audiences rolling happily ever after - - at any rate … the splendid musical will conclude Wayside’s fine summer season” (Keating. “Wayside Review.” TWaS. 20 Aug. 1970).

In the non-performing area of the Theatre’s history, it seems that at this time the organization did not have a Board of Directors. (SEE Appendix: Board of Directors). One document begins, “A meeting of the prospective board members of the Wayside Foundation for the Arts was held in the rehearsal hall of the Wayside Theatre on December 4, 1969 at 8:00 p.m.” It appears that those in attendance were devoted supporters of the Theatre and brought varying backgrounds to the group. At this meeting, Slavet spoke briefly of the Theatre’s history, the background of the Wayside Foundation, and expressed a need for the creation of a “board of directors made up of area residents.” Slavet did not have much confidence in advisory groups, as their power was limited. He strongly felt the need for a “board which is committed to the growth of the Wayside Foundation for the Arts – both financially and in service” whose goal is to make the arts “an integral and vital part of the growing community.” If this is the case, then a Wayside Board of Director was created some years after the founding of the Theatre. Leo Bernstein indicated that he “is most happy to donate the property and buildings for use by the Wayside Foundation for the Arts and to make other financial aid available to help further the work of the arts center when possible.” Bernstein adds that “he wishes to be just a member of the board, not an officer of the organization” as he felt this center for the arts should be the “community’s responsibility.” The document makes mention of a discussion regarding the goal of the arts center (e.g. the theatre): should it be change, or to preserve; how to meet the needs of the community, and the like. While no firm decisions are mentioned in the document, it was agreed to schedule another meeting in March (of 1970). (Document, “A meeting of prospective ….” 4 Dec. 1969).